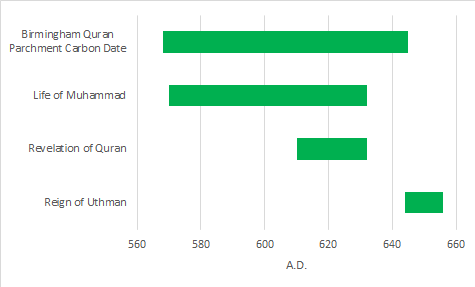

The world of Islamic scholarship was jolted in recent weeks by the age of the parchment from an early Quran fragment. The pages had been sitting in a University of Birmingham library for almost a hundred years, and only recently piqued the curiosity of scholars. According to radio carbon dating, the parchment was made between 568 and 645 AD. This is a potentially significant finding because according to Muslim tradition,

This timeline shows how it all fits together:

Some conservative writers, Pamela Geller, for instance, have noted that the finding “challenges Islam’s origins.” Certainly if parts of the Quran existed before the traditional date for the revelation of the Quran to Muhammad, or even before Muhammad was born, that would shake the roots of Islam and cast aspersions on Muhammad’s claim of divine revelation. While that's consistent with the radio carbon dating results, it is by no means certain. It’s only one of several possible conclusions that can be drawn. Others include,

I hope we'll hear more about the Birmingham Quran in the months to come. It would be interesting to see if there are other tests that could be applied to determine whether the parchment was reused or the ink was from a later date.

Saud al-Sarhan, the director of research at the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, said he doubted that the manuscript found in Birmingham was as old as the researchers claimed, noting that its Arabic script included dots and separated chapters—features that were introduced later. He also said that dating the skin on which the text was written did not prove when it was written. Manuscript skins were sometimes washed clean and reused later, he said.

Michael Isenberg is the author of Full Asylum, a novel about politics, freedom, and hospital gowns. Check it out on Amazon.com.